Emilio Ambasz and the Universitas Project

When I was getting my MFA in graphic design, I also got a concentration in critical studies. This meant that for two years, the first half of my weeks were spent in studio and design courses and the back half of the week was in art history, philosophy, and critical theory courses. I loved it. It took me a while to reconcile what often felt like an intellectual whiplash where the two sides of my week seemed like they were not in dialogue with each other in the way they could or should be.

I remember very clearly the class where suddenly everything clicked and I better understood the often unseen connections in my studies. In my aesthetics class, we were reading the French philosopher Louis Althusser’s 1970 text, Ideology and the Ideological State Apparatus where Althusser wrote that ideologies are formed not in the mind, but in our actions; in other words, he saw ideology as inherently material. “Ideologies do not obscure reality,” he wrote, “but rather creates new realities.” This happens, I saw immediately, through design. It is through design that ideology becomes reality. I spent a lot of time thinking about these ideas, researching the history of ideology and the built environment in hopes of writing about it at length. I never wrote the essay but in that research, I stumbled upon The Universitas Project, an ambitious project organized by the then-young architect and curator at the Museum of Modern Art Emilio Ambasz.

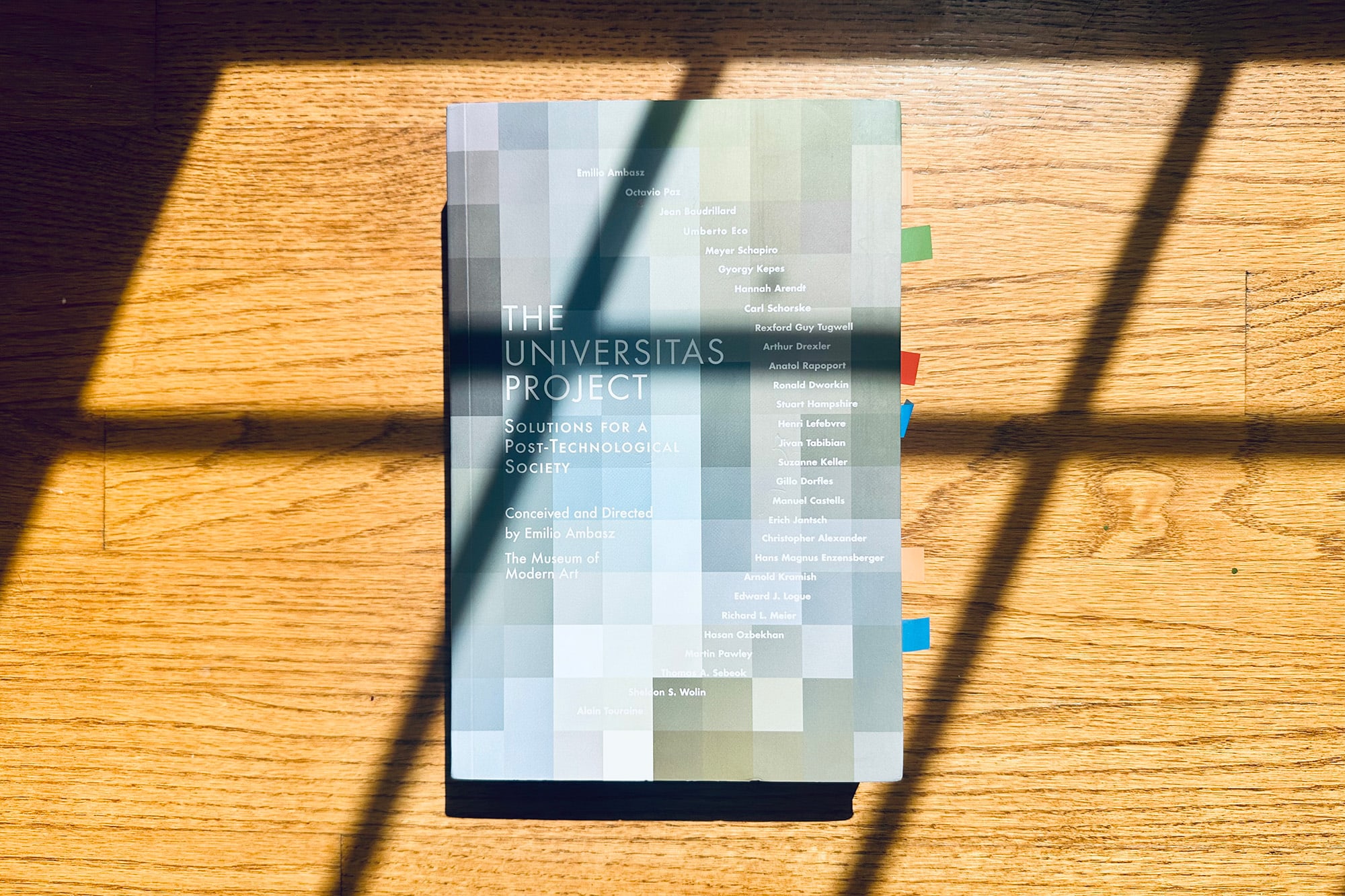

Ambasz wanted to create a “new type of University concerned with the evaluation and design of our man-made milieu.” Perhaps sensing the burgeoning Anthropocene, Ambasz saw the artificial world slowly consuming reality and believed that design played a critical role in that transformation. In 1972, he organized a two-day symposium in New York called The Universitas Project: Solutions for a Post-Technological Society, inviting philosophers, designers, architects and scientists — including people like Jean Baudrillard, Umberto Eco, Hannah Arendt, Richard Meier, and Christopher Alexander — to reflect on the new parameters of the designed, “artificial” world. The responses to Ambasz’s prompt and the proceedings from the symposium were collected in what was then known as “the black book”. MoMA formally published it years later. When I discovered it back in graduate school, I bought a copy immediately.

I spent a lot of time with The Universitas Project back then and lately have found myself returning to it again, finding it an ever more fascinating and relevant document and proposal1. In the introduction to the proceedings, Ambasz writes:

If design is understood, more broadly, as the endeavor by which man, consciously or unconsciously, creates structures that give meaning and order to his surroundings, it cannot leave aside matters of purpose and aspiration, and it must be concerned not only with facts but also with values and purport. Natural science deals with an order that can be assumed to exist already in the world, and to be independent of human activity. Its statements are properly declarative and empirical, whereas design statements, being about a man-made order, must also include the normative, and cannot be exclusively empirical and independent of the observer. Even when the design endeavor pretends to operate in strict adherence to the standards of objectivity and externality of a natural science, it will not be able to exclude matters of value; for when such standards are applied not to a natural but to a man-made order, the scientist’s commitment to the given, his fidelity to things as they are rather than as one would like them to be, will function, unacknowledged, as the guiding ethical principle. This has the effect, in our present situation, of conferring on the processes of technology the status of a force of nature, and thus discouraging any attempts to control them and change their course. Such “scientific objectivity” is therefore not really objective but plumps for the continuation of ongoing processes, the future as a prolongation of the present.

The future of the man-made milieu does not merely unfold from the present; one cannot predict it from a set of initial conditions as one predicts the future state of a mechanical system. Rather, it depends on what we think it ought to be and what we do to bring this about. The envisioning of alternative futures, which are not contained in the present but which are to be created, purposefully worked toward if they are found to be desirable, is fundamental to a design endeavor that is concerned not just with designing strategies and producing artifacts to meet a set of requirements, but with the larger task of synthesis of the man-made milieu, of giving meaning and structure to the productions of man.

It’s interesting to read this in a contemporary context where the increasing influence of artificial intelligence, of platform capitalism, of the threats to democracy that are exasperated by social media, of the ever-present climate crisis are top of mind for many. What do these mean for the designer? What do they mean for design? In the years since Ambasz wrote these works, design of all types has rallied around “problem-solving” as their mandate — it’s been tied up with business, with process, with emerging technology. Ambasz is arguing, I think, for another direction: design not just as problem solving but as culture-making — of creating meaning and value beyond the limits of the project at hand.

A great introduction to Ambasz’s work is Felicity Scott’s paper, On the “Counter-Design” of Institutions: Emilio Ambasz’s Universitas Symposium at MoMA. She writes:

According to Ambasz, MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design was in a privileged position to address such transformations on account of the nature of its object of study. For, as he explained in his opening remarks, “we have to deal constantly with the objects that man makes, with his architecture and his cities—and we have to deal explicitly with the socio-economical context to which they pertain.”6 If the socioeconomic context had not in fact been central to the museum’s concerns previously, it would be so for Ambasz because it was through the very conjunction of socioeconomic and design concerns that he traced a “complement between aesthetic and ethical evaluation.” But it was also evident to him that neither the intellectual tools nor the pedagogical institutions of contemporary design could adequately deal with the constellation of forces deriving from this socioeconomic context—what Ambasz referred to as the new “technological milieu,”a dispersed if totalized environmental system that was inextricably connected to the administrative and commercial apparatus. The tropes informing his concept of design—structure, process, meaning, and order—derived, as we shall see, from an already expanded disciplinary matrix within which this turn from certainty to doubt, and from discrete objects to those continually in process, seemed more possible to formulate and address.

Ambasz thought MoMA was in a position to promote and build upon these ideas because, as Scott notes, “neither the intellectual tools nor the pedagogical institutions of contemporary design could adequately deal with the constellation of forces deriving from this socioeconomic context.2” The academy — design education was we know it — was too focused on immediate goals. It was too siloed, too limited in its scope. Here’s Ambasz again:

[O]ld courses with new labels; or structural changes which are not substantiated by meaningful design philosophies and do not present a wholistic approach to the design of our environment can only be imputed either to cultural naiveté or to a deliberate attempt to protect the status-quo while simulating change by means of a novel jargon.

I found myself thinking of this line while reading this excellent Places Journal interview with Jorge Otero-Pailos on repairing architecture schools:

Schools have the responsibility to go beyond protecting the ideals of the current profession. They need to become laboratories for cultivating new ideals centered around care and repair, a new grammar through which students can make sense of themselves, their work, and its purpose in the world. Schools should develop the student’s capacity not only to question things as they are, but to propose and test alternatives. It is important that these experiments are not foreclosed too early with the reasoning that they have no immediate pragmatic consequence in the current profession. They need time to gestate. Ultimately, these small experiments can grow to be compelling enough to become models that the profession emulates and scales up further.

Design education, all too often (in my opinion), follows immediate market needs; jumping onto the next trend and forgoes the long-term thinking about both Otero-Pailos and Ambasz call(ed) for. I’m sure we’re all familiar with curriculum redesigns that lead to new class names without fundamentally rethinking what a student should be learning.

Matthew Holt, building upon much of Scott’s scholarship, writes in his paper The Black Book:

As made abundantly clear from the various contributions of the participants of the MoMA symposium, design and design education is uniquely positioned within this new informational, technical and communicational environment of the postindustrial: at once within it and yet able to conceptualize it; at once its most contemporary avatar and the radical proposer of alternatives to it. Unlike the Bauhaus and its successors, which, however brilliantly and however intelligently, primarily furnished products and training for the industrial economy, the university of design is to intervene at another level. Not only is the universitas to provide design and designers for the postindustrial economy but to illuminate—from the inside, as it were—the fault lines of this economy, expose its shortcomings, decolonize it, and provide it with ethical and aesthetic infrastructure, that is, a critical, pedagogical language sophisticated enough in both content and intent (a language severely lacking in the contemporary institution, including design schools). Thus we can take from these proceedings at least one aspect to focus on: the emphasis placed by many symposium participants, including the organizer, on providing alternative visions to the status quo via the conceptualizing and designing of the artificial milieu, and suggest this is an essential aspect of any new university—or similar institution—devoted to design. The scholarship, research and practice required to envisage and employ the “counterfactual” element of design is, I would argue, the foundation stone of any university education. It is an essential part of the understanding and creation of artificial environments—and the modes of information and communication needed to articulate them.

This does not mean, as often happens in the academy, that design should conform to the standards of other disciplines but rather that design is central, on its own, to these other disciplines. Holt continues:

Above all the symposium heralded an awareness that design knowledge—and therefore design education— is now the most essential form of knowledge, and not a subsidiary or adjunct to other disciplines. The event heralded a “post-technological” and “post-scientific” future for the university.

As I find myself thinking about the Universitas Project again, I’m continually struck by how much I’ve internalized the ideas and mission, how much of it has influenced how I teach (and try to teach) design today:

Instead of seeing design as the production of commodities, it needs to be understood as inventing, creating and sustaining artificial environments. In the socialist tradition, whether the Arts and Crafts movement or the Bauhaus and beyond, design has always been taken to be an intervention in the shaping of artefacts for industry or refining the manner of their consumption. William Morris, for example, believed properly designed artefacts ameliorate and improve existing conditions, but would not have considered design as counterfactual communication or as planning ephemeral and intangible information and communication services and systems. In a very real sense he could not have. That informational characteristic of political economy (post-handicraft, post-product, even post-object)—the “political economy of the sign” as Jean Baudrillard, a contributor and participant of the 1972 conference, calls it—only effectively transpires in postindustrial societies. In fact it could be argued that design in this sense—“metadesign” (Busbea 2009)—has only come into existence in the mid-Twentieth Century. Design understood in its diverse meanings and above all not restricted to artefact design is a contemporary phenomenon. If alternatives to capitalism—or alternative forms of capitalism—are to be considered, let alone embraced, an acknowledgement and understanding of this environmental sense of design is essential.

Scott calls out Ambasz’s definition of the designer as critical to imagining the future:

Unlike the scientist who, Ambasz claimed, “seeks a grasp of the actual,” the ethic of the designer was to project an alternative (and better) future. “The future of the man-made milieu,” Ambasz insisted, “does not merely unfold from the present; one cannot predict it from a set of initial conditions as one predicts the future state of a mechanical system.” Alternate futures, he explained, distancing himself from futurology, are not contained in the present but must be “created.”

All design, of course, is an act of future-making. In the age of tech-determinism, the role of the designer becomes even more important: it is the designer (and the artist, the writer, the poet, the philosopher) who can imagine different futures. And then help make them reality.

As I wrap up the semester and look towards the summer, I’m finding myself once again returning to Ambasz’s incredibly prescient project. In many ways, the ideas embedded in it feel more important now than ever.

-

Two things caused me to revisit it: Matthew Wizinsky’s book Design After Capitalism references it and last year, I had Carson Chan, the director of the Ambasz Institute at MoMA on Scratching the Surface. ↩

-

Ambasz, generally, is an interesting figure. He was an early curator at MoMA and a leading figure in thinking about what was later referred to as ‘green architecture’. He continues to practice today. Here are some interviews with him. ↩