Wes Anderson’s Reflexivity

This past week I read Matt Zoller Seitz’s The Wes Anderson Collection, a book of essays and interviews with the director of some of my favorite films. I bought the book when it was released back in 2013 but never say down to actually read it, cover to cover, until now. It truly is a great resource of behind the scenes images and insights from Anderson on the making of each film from Bottle Rocket through Moonrise Kingdom.

However, what really struck me as I read each chapter was how reflexive a director Anderson is, continually giving the viewing some insights into each film’s making. Very early in the first interview, Anderson references the famous Godard quote, “Every film is a documentary of its actors.” Zoller Seitz includes Jacques Rivette’s similar thought: “every film is a documentary of its own making.”

The reflexive themes begin in the introduction by Michael Chabon, commenting on the assertion that Anderson’s films are artificial—perfectly designed sets reminiscent of Joseph Cornell’s assembled boxes. Each scene perfectly framed, each detail designed to Anderson’s specifications. Chabon argues that this artificiality actually makes the films more authentic:

The things in Anderson’s films that recall Cornell’s boxes—the strict, steady, four-square construction of individual shots, by which the cinematic frame becomes a Cornellian gesture, a box drawn around the world of the film; the teeming, gridded, curio-cabinet sets at the heart of The Life Aquatic, Darjeeling, and Mr. Fox—are often cited as evidence of his work’s “artificiality”, at times with the implication, simple-minded and profoundly mistaken, that a high degree of artifice is somehow inimical to seriousness, to honest emotion, to so-called authenticity. All movies, of course, are equally artificial; it’s just that some are more honest about it than others. In this important sense, the hand-built, model-kit artifice on display behind the pane of an Anderson box is a guarantor of authenticity.

Anderson seems continually interested in reminding the viewer they are watching a film. We first see this with Rushmore’s chapters, styled with the curtains opening to mark the next act. At the risk of taking you out the story’s flow, Anderson drops back in, reminding you this is a thing people made; you’re watching a story.

This reflexivity perhaps becomes most obvious with Bob Balaban’s character in Moonrise Kingdom. Balaban is a part of the film’s world but also its narrator, continually breaking the fourth wall and talking directly into the camera. In one scene, we actually see Balaban light the scene, from a spotlight off camera before beginning his narration. You are seeing the storyteller and his preparation in its retelling.

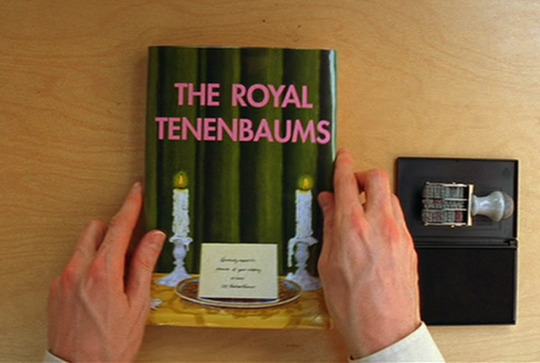

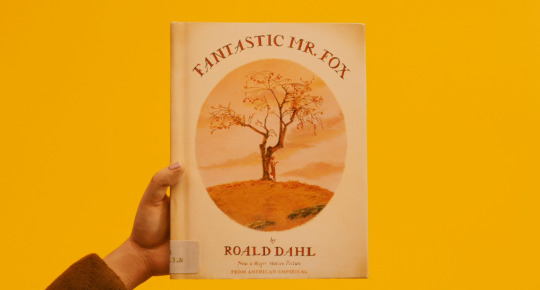

We see this type of reminder again and again in his use of books and stories to begin his movies. Both The Royal Tenebaums and Fantastic Mr. Fox’s title sequences include the film’s name on a book cover. A story is beginning, Anderson seems to be telling us. In the section on Fantastic Mr. Fox, Zoller Seitz writes:

You’ve got the curtains in Rushmore, You’ve got The Royal Tenebaums presented as a book, the fiction that’s being written in The Darjeeling Limited, the documentary films in The Life Aquatic and of course Fantastic Mr. Fox, which you acknowledge from the first frames of the film as being a book…a lot of people complain that these kinds of devices remind them that they’re watching a movie, or that in literature they remind them that they’re reading a book.

Anderson responds with his love of Stefan Zweig’s books which often featured nested stories: a book that begins with one person telling somebody else about it. Zweig’s story structure, of course, was the inspiration for Anderson’s future film The Grand Budapest Hotel which nested stories within stories and opened with that acknowledgement.

Though Anderson has always used the frame as part of the story, it was never more connected than in The Grand Budapest Hotel. Anderson has a deep knowledge of film types and film ratio and has use different ratios to help frame his stories but in Grand Budapest, he used three different film ratios to represent the different points in time, or the stories within stories. The ratios helped orient the view in what time period they were in, what story was being told.

In a piece for The New Yorker, Richard Brody noted the film’s reflexive themes:

This isn’t Anderson’s most personal film, in the strict sense, but it is, alongside “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou,” his most reflexive one—even more so because the new film exposes the inner workings not just of his practice of filmmaking but of his sensibility.

The Life Aquatic, of course, is literally a film about making a film, giving us insight into how Anderson thinks about his movies but like the Rivette quote, each of his films seem to be about themselves. “It’s not what the movie is about,” Roger Ebert famously wrote, “it’s how it is about it.”

Anderson is continually giving us glimpses into his process. It’s honest in it’s artifice and open in its handmade quality. He’s constantly reminding us we are watching a movie and letting us see the hand of its creator.