Maybe I still like design?

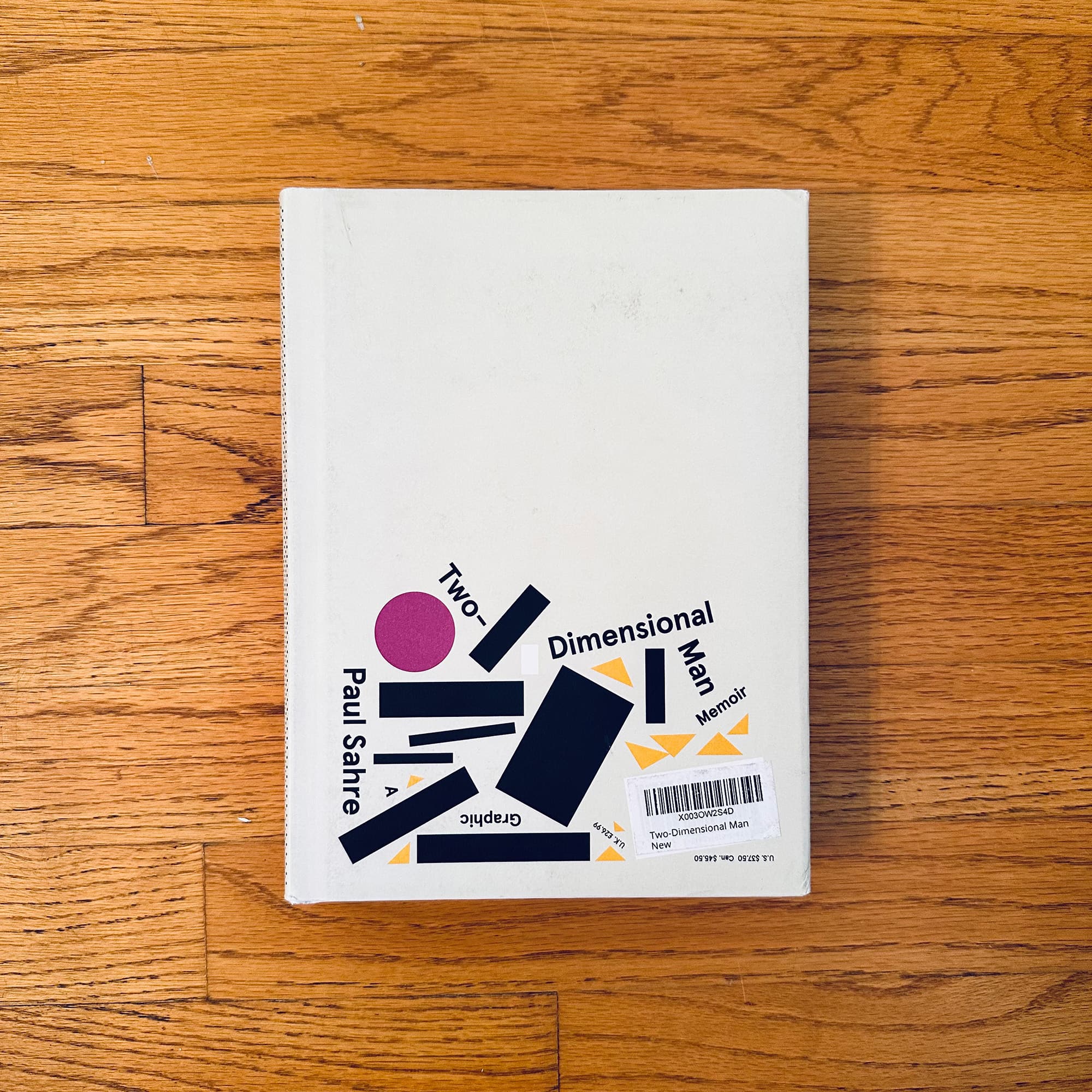

One of my favorite ways to spend the first few weeks of summer break is catching up on the books that I let pile up around my desk in the studio over the past few months (sometimes years!). These are the books that are usually design related or work-adjacent but not directly related to projects, research, writing I’m doing. Because of this, they keep getting pushed to the side in favor of books I need to read for work. Sometimes, however, when I pick up one of these books after the semester ends, it turns out to be just the book I needed at just the right time. This is how I felt reading through Paul Sahre’s 2017 memoir/monograph Two Dimensional Man. This is a book I’ve been meaning to read since it came out and I only just got to it now but as soon as I picked it up a few days ago, I tore through it, unable to put it down.

I’ve long been interested in the form of monographs and often think designers don’t experiment in the format enough: all too often they become a glorified portfolio — a collection of images I can see online printed in higher resolution on nicer paper. The monographs that mean the most to me, however, try to do something else: they tell a story, the show the work in a new way, they make an argument for how this particular body of work goes together. SMLXL, of course, is an example of this. So too is 2x4’s abstract it is what it is (especially when paired with Michael Rock’s Multiple Signatures) or Experimental Jetset’s Statement and Counter-Statement. I like when other voices are brought in, like Metahaven’s Uncorporate Identity or even when they’re put together posthumously like the great Tibor Kalman book.

When I’m not reading fiction, my preferred genre is biography and memoir. I like understanding how a person became the way they did. I like the retroactive “aestheticization of life”, as Hua Hsu put it. Paul Sahre’s book is more memoir than monograph. Or perhaps more acurrately: it’s a monograph wrapped in memoir. There’s more text than images here and Paul’s prose moves seamlessly from design projects to his personal life, covering his early childhood in upstate New York, his relationship with his family, romantic relationships, and his college years. Two parallel narratives emerge: the untimely death of his younger brother with Paul discovering his voice as a designer. These narratives don’t seem like they should go together, yet it never feels forced. Paul somehow made it all work.

As you read the book, you follow Sahre’s ups and downs from his early college classes in design to failed projects to personal projects that led to real jobs. Through it all, you see in falling in love with graphic design, design, in turn, helped him find his place in the world. I couldn’t help but reflect back on my own journey in design. Like Paul, design was a lifesaver for me: a way for me to relate to the world around me. Reading about his time in college forced me to reflect on my own, when the world was in front of me and I was excited to design everything and anything. I was reminded of early jobs that didn’t pan out as planned and the energy I once had for side projects, personal projects, and collaborations with friends.

I probably shouldn’t admit this but in the last few years, I sometimes feel like I’ve grown disillusioned with design. As graphic design has evolved — as it’s been co-opted by design thinking, corporate interests, and human-centered methodologies — conversations around contemporary design can bore me. I find myself fantasizing about ways out. Maybe I could be a journalist? Or a curator? Could I write about other things, besides design? Or shift my focus to the arts, to culture, to anything other than what I’m doing. When I was in school, design felt more like a cultural invention than the pseudo-engineering problem-solving it’s often defined as today. The work that interested me fifteen years ago (that still intersts me) is harder to do now. It’s certainly not where the money is anymore.

I remember seeing Sahre’s work in college and loving it immediately. It was the kind of work I wanted to do: smart and witty, visually interesting and experimental. Reading Two Dimensional Man — which wrapped this work in a deeply personal story — took me back to that time when design excited me. It reminded me of why I fell in love with it in the first place. It made me think, for the first time in a long time, like I wanted to design something, even if just for myself. It made me think that maybe I still wanted to be a designer.

As graphic design increasingly moves digital, as the nucleus of the industry shifts to project design, Sahre has maintained a deeply personal practice that feels simultaneously fresh today and harder than ever to maintain. His book, then, serves as a guide for those of us who never want to forget that design, too, is expression. That behind the work, there’s always a person.