A love letter to HTML

I have a new essay for Untapped on building websites with HTML and CSS for twenty years. Here’s how it opens:

A few months ago, I needed to make some changes to my website. What started as simple content edits—updating my biography, adding projects to my portfolio—quickly spiraled into a bigger project. New content types required new templates. My website is hand-built; I don’t use a content management system or an off-the-shelf-platform. Before I knew it, I was staying up late, rethinking the content architecture from the ground up.

I’ve been making websites for 20 years, and have been building and rebuilding my own website for just as long. I taught myself HTML when I was 15 by clicking “View Source” in my web browser, then copying and pasting snippets of code to hack together simple web pages until they looked good and functioned properly. Since then, I’ve used HTML (albeit in a more sophisticated capacity) and CSS, another coding language, to make nearly every website I’ve ever worked on. It recently dawned on me that many of the design tools I used when I began my career are now obsolete or have radically changed. Updating my website these last few months, I sometimes felt like I was 15 again.

Websites are perhaps the only type of design project I can work on the same way I did when I was a teenager. Figma didn’t exist, nor did any of the other upstart design software companies that have come and gone over the years. The Adobe Creative Suite looks increasingly unrecognizable to me, and I’m often unable to open files I created in previous versions. As an undergraduate design student, I took three required classes on Adobe Flash, software that, at the time, felt like the future of web design before it fell out of favor a few years later.

It’s a weird piece, honestly. It’s one of the more personal things I’ve written but it’s also a piece of technology criticism, a meditation on tools, and how we make things that last. In addition to my own story, I spoke to Paul Ford and Laurel Schwulst for the piece and was happy to have their voices woven into the narrative. You can read the whole thing here.

I’ve been wanting to write a version of this piece for a few years but could never get it quite right1. I didn’t want this piece to be nostalgic; to feel like a call to return to some previous web era. I didn’t want it to read as a value judgement nor as a call to action for everyone to build their own websites. The crux, as the piece opens, was this realization that I was still building websites in essentially the same way I always had and there was no other process in my work that has remained so unchanged. We don’t think of designing for the web as lasting, yet here we are.

This comes at a moment when designing for the web feels like it’s falling out of favor. When I was in school, the debate was whether designers should learn to code. In many ways, that debate is still ongoing — it seems many design programs are teaching less coding again, as designing websites isn’t as sexy as designing an app. And when you are designing an app, design students can do some complex interaction in a Figma prototype. It seems to me that something is lost in this shift, there still must be some value in understanding HTML and CSS. There still must be some value in the open web.

Last year, Robin Rendle wrote about how embarrassing the web has become, bemoaning the lack of design, details, and care it seems to have lately. He’s not wrong. We’ve — as designers, design institutions, etc — turned our back from the web in many ways. I’ve long felt a desire to return to the open web — I wrote about right here on my blog five years ago!

I was pleased to see this piece come out just a few days after Kyle Chayka’s latest New Yorker column, on the return of homepages:

The major social platforms operated for a long time like digital big-box stores for media content, offering a little of everything all at once. Twitter, especially, served as a one-stop shop for news and entertainment among a certain kind of very online user. In the twenty-tens, the conventional wisdom was that content was best distributed to consumers by social platforms through algorithmically personalized recommendations. You read whatever news surfaced in your Facebook or Twitter feeds. News articles circulated as individual URLs, floating in the ether of social-media feeds, divorced from their original publishers. With rare exceptions, home pages were reduced to the role of brand billboards; you might check them out in passing, but they weren’t where the action lay.

Now digital-distribution infrastructure is crumbling, having become both ineffective for publishers and alienating for users. Social networks, already lackluster sources for news, are overwhelmed by misinformation and content generated by artificial intelligence. A.I.-driven search threatens to upend how articles get traffic from Google. Text-based media have given way to short-form videos of talking heads hosted on TikTok, Instagram, or YouTube. If that’s not how you prefer to take in information, you’re out of luck. Surrounded by dreck, the digital citizen is discovering that the best way to find what she used to get from social platforms is to type a URL into a browser bar and visit an individual site. Many of those sites, meanwhile, have worked hard to make themselves feel a bit more like social media, with constant updates, grabby visual stimuli, and a sense of social interaction. Patel told me, “What we needed to do was steal moves from the platforms.”

Perhaps the platform era caused us to lose track of what a Web site was for. The good ones are places you might turn to several times per day or per week for a select batch of content that pointedly is not everything. Going there regularly is a signal of intention and loyalty: instead of passively waiting for social feeds to serve you what to read, you can seek out reading materials—or videos or audio—from sources you trust. If Twitter was once a sprawling Home Depot of content, going to specific sites is more like shopping from a series of specialized boutiques.

Chayka’s tackling a parallel idea to my piece: as the web (and our digital lives) are increasingly platform-ized, we’re continually at the mercy of those platforms. Chayka looks at this through the lens of homepages, which had largely been overlooked as traffic increasingly was coming from social feeds, are important again in a way they haven’t been in years. As these platforms crumble, we’re due, I think, for a web renaissance. As Paul Ford told me, “The web is still the best document-distribution platform in the history of the world.”

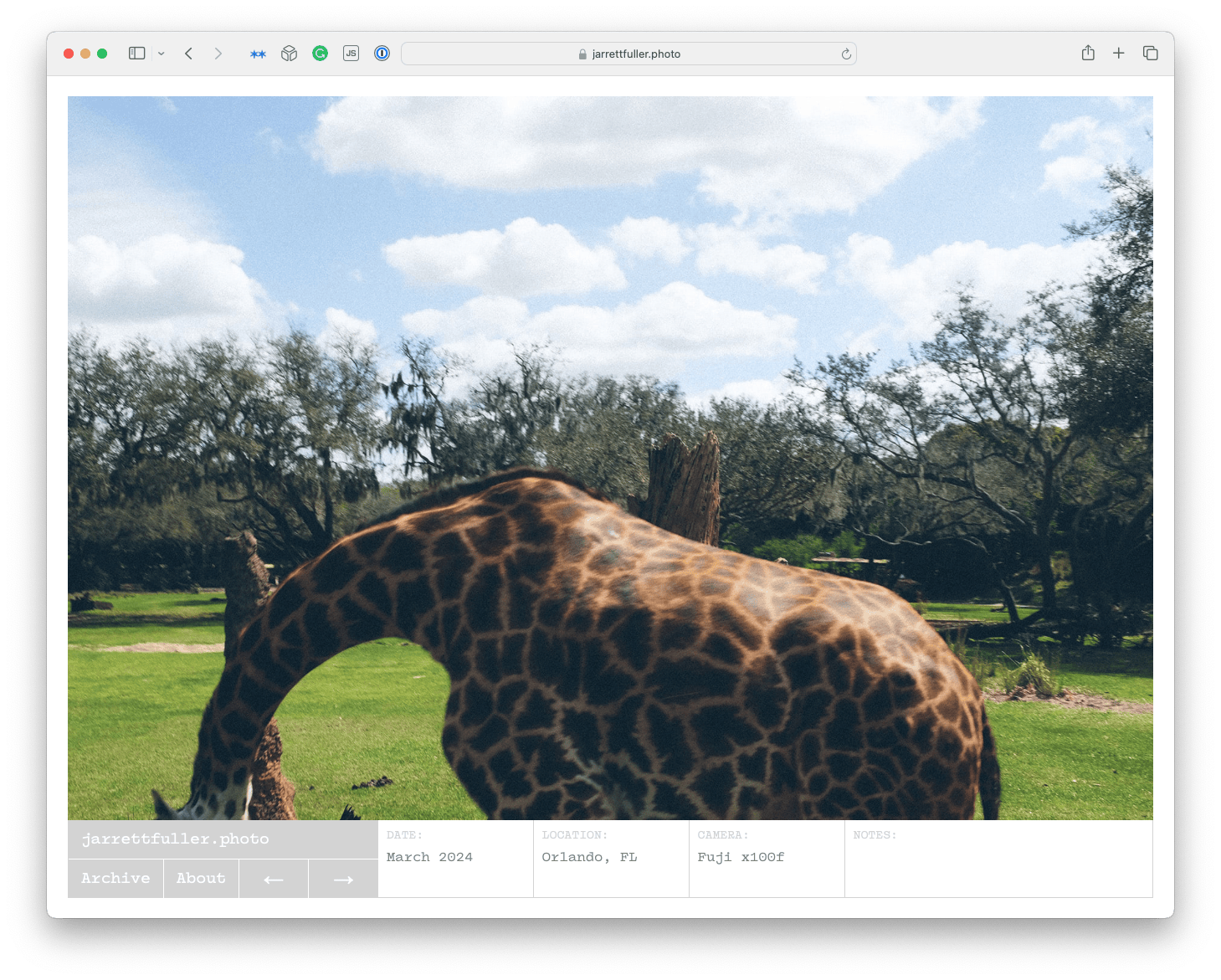

This is why I still build my websites myself. This is still why I still publish on this blog. This is why everyone still is logged on my own website. This is also why, after posting photography on Instagram for the last decade, I just launched a brand new website: jarrettfuller.photo.

Over the last few years, I’ve increasingly felt like Instagram was not the place to post and share photography anymore. I always include recent photographs in my newsletter but wanted a dedicate place for photography. So as I was writing about HTML, I was building a brand new website with HTML and CSS, just like I always have.

I’ve been interested in photography, like HTML, for twenty years. Its one of my longest running hobbies and much of my early photographic education came from photoblogs. Daily Dose of Imagery and Naz Hamid’s Absenter (both no longer active) were daily visits for me. This new site, which is a static site powered by Jekyll like all my sites are as are, is an homage to those, designed based on my memory of the feeling of those sites.

Each image is on its own page with metadata on the bottom. There’s an RSS feed if you want to keep up with it. Maybe I’ll experiment with email too. I don’t suspect it’ll get the traffic an Instagram account would but that’s okay. Part of it exists just so I could design a new site. Part of it is so I can own my own turf. And part of it is because I still love the power of the open web.

-

So much gratitude for my editor and friend Tiffany Jow for talking about these ideas with me and helping to sharpen its angle. And then for agreeing to publish it. ↩