Perfect Days

Wim Wenders’s latest film, Perfect Days, is now available for streaming on Hulu1. I’m a big fan of Wenders’s films, ever since watching Paris, Texas almost fifteen years ago, and was excited to catch this latest. The film stars the well-known Japanese actor Koji Yakusho as Hirayama, who spends his days cleaning public toilets in Tokyo. The film has its origins in a public toilet project Japan initiated ahead of the 2020 Olympics:

Koji Yanai, the son of the founder of Fast Retailing (the sprawling clothing giant best known for its Uniqlo brand) and a senior executive officer there, had spearheaded the public toilet project to be an architectural display of “Japanese pride.”

“If I say Japanese toilets are world number one, no one will disagree,” Yanai said in an interview late last year. He had recruited the architects to design the public buildings with a distinctive aesthetic that would make them as much art as public utility.

Originally built to welcome the world to Japan for the summer Olympic Games scheduled for 2020, the toilets did not get their moment because the pandemic forced the postponement of the Games to 2021, which were then staged without spectators.

After the quashed Olympic debut, Yanai was seeking another path to promotion. He reached out to Takuma Takasaki, a screenwriter and creative director at Dentsu, Japan’s largest advertising firm, to help hatch a plan to champion the toilets internationally.

Wenders, who has a long love of Japan, was brought on and co-wrote the script based on this prompt. But the movie, a quiet character study, slowly builds into a mediation on what it means to live a good life. Hirayama lives in a small apartment and spends his free time taking photographs, listening to music on cassettes, and reading used paperback books. I appreciated Sam Holden’s look at the role of analog media in the film:

The Tokyo depicted in Perfect Days is a thoroughly analog world of places that flow into one another in a continuous, fluctuating medium of experience. In one of the first scenes, Hirayama is awoken before dawn on the tatami floor of his tiny second-floor room by the faint sound of a broom sweeping at the shrine across the street. He lives in one of the once-ubiquitous uninsulated wooden apartments, where the outside can be heard, seen, and felt, and transplanted ferns can be tended next to the big window that looks out at the canopy over the shrine. Upon leaving home, he moves through the city in interludes spent listening to tapes as he loops around the urban core along the metropolitan expressway, or slow tracking shots of his bike coasting through winding alleyways to the bathhouse and over bridges to his favorite small bars. The medium of transmission that melds life into a continuous signal is the bathwater that sloshes between neighbors, the light and shadows, the wind rustling the leaves of a shrine, the smiles on familiar and unfamiliar faces that indicate you are part of this world. To the modern eye, the continuity of his life world has the effect of elevating his habits from quirky idiosyncrasies to a monk-like way of being. He appears to inhabit the city on a spatial plane that eludes ordinary people, and yet all he’s doing is being present in mind and body in his environment.

In this way, Perfect Days, at times, feels like an act of media criticism or urban reflection. Indeed, in The Architect’s Newspaper, Jack Murphy noted its similarities to Beka & Lemoine’s2 film Moriyama-San:

Upon examination, Perfect Days possesses many similarities to Moriyama-san, a 2017 film by architectural filmmakers Bêka & Lemoineabout one week in the life of Mr. Moriyama, the single, older Japanese man who lives in a house of deconstructed rooms widely known as the Moriyama House, completed in 2005 by Ryue Nishizawa of SANAA. Moriyama is a free spirit, and the film follows his habits, from noise music to books. There are clear stylistic, soundtrack, and plot differences, but the main character’s vibe is strikingly similar: Both like reading in contorted positions, caring for plants, and staring at shadows. Even the name of the central character is similar.

Wenders spoke about how he wanted Hirayama to be a monk-like character here and expands upon these ideas in his interview with Tim Brinkhof for Triangle:

But—and this is what elevates Perfect Days as a piece of cinema—things are not as straightforward as they appear. Hirayama isn’t (yet) a buddha, and his life isn’t entirely free from pain. Though his backstory goes largely unexplained, certain scenes—an encounter with his estranged and wealthy sister, a longing look at a waitress—suggest Hirayama isn’t guided by the light so much as he is haunted by the past. I discuss this and more with Wenders in the following interview, which began with my asking whether Wenders himself knows more about the protagonist’s past than what he shows on-screen:

“Indeed, there was a backstory,” Wenders answered. “I had to write it down, at least for myself, to imagine the character of Hirayama when we wrote the screenplay. And later, I figured, Koji Yakusho would eventually ask me the same question you just did, as an actor. So I wrote five pages to know for myself who Hirayama was. I wrote it as a verbal account by Hirayama himself, looking back at his life, told to me in the first person.

In The Brooklyn Rail, however, Nolan Kelly questions the simplicity and neorealism the film professes:

But although Hirayama’s daily rituals are granted a similar reverence to neorealism’s heady early days, a sense of struggle is missing. Menial labor is grinding, even when well-organized and well-compensated. To dedicate much of one’s life to the thankless service of others can be frustrating and humiliating, and such invisible labor rarely inspires one to do one’s best. In spite of all this, cleaning toilets seems almost placidly joyful for Hirayama, who has jury-rigged several tools to get at obscure corners and crannies of his glistening domain. And though his cleaning practice offers a chance to show us his pride and work ethic, it’s never actually difficult, because the toilets are never actually dirty. When he gets off the clock, he makes daily visits to his local bathhouse, dines out nightly, and even has time to keep up with modern literary trends—the shopkeeper commends him on his choices when he swings by the bookstore. In short, this vanishingly rare cinematic treatment of the underclass seems instead like something of a red herring. Though you would think no work is lower, Hirayama’s lifestyle seems delightfully comfortable—even in the socioeconomic sense of the word.

What I liked about the movie was its patience. There are small ruptures in Hirayama’s routine but the film maintains a pacing, a simplicity, that echoes his own life. Here’s Bilge Ebiri for The Criterion Collection:

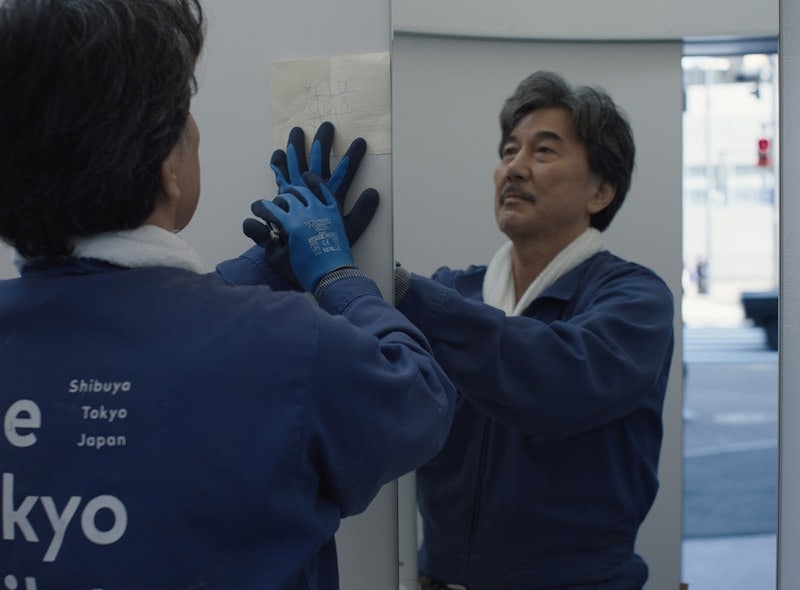

Yet there’s nothing rushed or undernourished about Perfect Days. In fact, it might be the most patient film Wenders has ever made. The camera takes its time lingering on Hirayama’s face and his methodical, graceful movements, watching him as he quietly goes about his daily routine and his job as a bathroom cleaner. He wakes up every morning, spritzes his flowers, puts on his Tokyo Toilet jumpsuit, drinks his breakfast, and drives his cramped van through the streets, listening to old cassette tapes of the Velvet Underground, Patti Smith, and Otis Redding. At each stop, he shows dedication to his work: he wipes down every corner of the bathrooms, diligently cleans the retractable bidets, and even uses a little mirror to ensure he has covered all the tough-to-get spots.

As a lover of routines, watching Hirayama’s repetitions became a meditation of sorts for me, a father of two children who rarely has the simplicity and structure the film presents. But when I finished watching it, I related to the desire. I got into bed, turned on my light, and opened my used paperback to read until I fell asleep.

-

It’s a small thing but I love that this is on Hulu. I was thinking recently about being in college when Netflix launched its streaming service and how it was there that I saw movies like 8 1/2, The Searchers, Ken Burns Jazz. There was a wealth of film history, right there, on Netflix. It’s harder, it seems, to find under-the-radar and/or older movies on the streaming services these days so I love that the latest Wenders is on Hulu, not just, say, The Criterion Channel. ↩

-

I spoke to Beka and Lemoine on Scratching the Surface last year. ↩